Can Europe Militarise its Way Out of Manufacturing Stagnation?

European manufacturing faces stagnation, with rising costs and regulatory burdens limiting growth. While some propose increased military spending as a solution, data from the Manufacturing Industry Output (MIO) Tracker suggests otherwise. Unless military investments prioritize domestic production over imports, remilitarization is unlikely to drive significant manufacturing growth in Europe.

![[object Object]](https://admin.industrialautomationindia.in/storage/articles/article-Obqhpj96WBjaz5QpOGLrWQ34mC0yBMQsUSf2BDlS.jpg)

Strong manufacturing growth through remilitarisation appears unlikely, says Jack Loughney.

The major regions of Europe’s manufacturing economy are stagnating. Huge regulatory burdens, rising energy and labor costs, and lower productivity are pushing up production costs. Coupled with a reduced appetite for risky capital investments and a host of other more minor issues, the largest producers within Europe are struggling to compete with the rest of the world when it comes to growth in the manufacturing sector.

tal manufcaturing is significantly below the US

This raises the question of what Europe can do to pull itself out of the current manufacturing malaise. One proposed solution is to spend more on defense. But, can this prove successful? I have conducted analysis based on our Manufacturing Industry Output (MIO) Tracker in order to try and provide an answer. The graph below shows the combined total MIO output of the 4 largest NATO contributors (in dollar terms) alongside the overall growth of the four regions combined illustrating the stagnancy and slow growth of the region after the post-pandemic recovery.

One of the key advantages the US has over Europe is the giant and military industrial complex and huge government contracts in the defense and aerospace sectors, which spill over into broader industrial production. One of the suggested advantages for the manufacturing economy at large is that, in theory, if you increase military spending it will filter through to other sectors and boost overall production. For example, metals, plastics, electronics and components are required to manufacture planes, ships, drones and weapons, and machinery is required to manipulate and build the parts for the defense industry. Fortunately, by levering data from the MIO tracker and figures provided by NATO we can examine whether this theory works in practice.

Comparing NATO spending vs MIO production

According to NATO, the US spent an estimated total $86 billion on military expenditure in 2023. In comparison Germany France Italy and the UK combined spent a combined $22.2 billion.

MIO production for these four major European economies (France, Germany, Italy and the UK) totalled $4.5 trillion in 2023, while the US had a production value of $6.3 trillion. This is not a huge difference in total production, however, comparing these figures with total military spend, the US produced 1.4x as much but spent 4 times as much on its military.

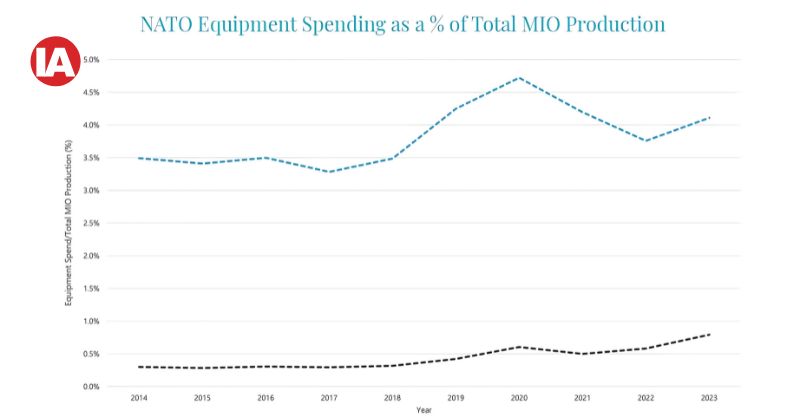

If we compare specifically military equipment spending vs manufacturing production between Germany and the US (US in dollars, Germany in euros), we see a marked difference in the overall split. The US maintains a ratio of over 3% of its total manufacturing production in military equipment spending, whereas Germany’s spending has remained below 1% between 2014 and 2023. This graph is consistent with other large European economies, which also lag behind the US on military spend.

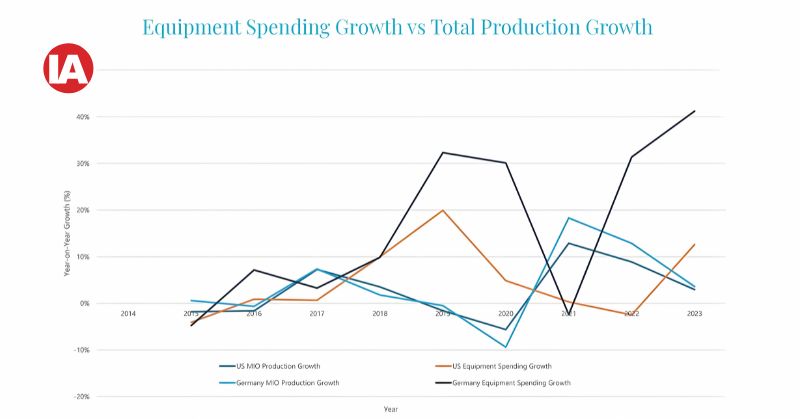

Plotting production growth vs total MIO production growth provides us with some interesting information. Namely, higher military spend does not necesarrily correlate with an increase in total production. German equipment spending grew in excess of 30% in four of the past five years with minimal effect on total production.

Given the small % that equipment spend represents compared with total MIO production this is perhaps unsurprising. It’s significantly easier to grow in % terms when you aren’t spending much overall. However, this calculation doesn’t paint the whole picture.

military spending and total production growth

European military spending is not spent on European military goods

The crux of the issue is that historically the European regions have imported a large proportion of the military equipment from other regions. Namely, the US. According to SIPRI (Stockholm International Peace Research Institute), “Arms imports by the European NATO members more than doubled between 2015–19 and 2020–24 (+105 per cent). The USA supplied 64 per cent of these arms, a substantially larger share than in 2015–19 (52 per cent).”

European members of NATO pledging to increase their military spending is significant and its importance should not be understated, but whether the EU can militarize its way out of its economic difficulties will very much depend on whether military spending is on European production. If not, it will just be a boon to other countries.

Comparatively, the US (based on import data on trading economics) spends around $600 million a month importing military aerospace and other military equipment (around $5 billion to $10 billion of imports per year). If we assume the higher end of the estimate, this is still less than 5% of total US military spend being on imports versus domestic production.

An EDIS Joint Communication (European Defense Industry Strategy) issued in March 2024 stated that “Between 2021 and 2022, there has been a 7% increase in the procurement of new equipment, but only 18% of the total equipment spending was devoted to EU collaborative defence equipment procurement in 2022 , far below the current 35% collective benchmark set by Member States.” (Page 4) The 35% commitment was agreed in 2007, so over 15 years later they still haven’t met the benchmark. The proposal “to shift towards a sustained, long-term demand signal to the EDTIB (EU’s Defence Technological and Industrial Base), it is proposed to Member States, to achieve the goal of procuring at least 40% of defence equipment in a collaborative manner by 2030” seems difficult to achieve at best.

What is the takeaway?

The concept that a manufacturing economy’s position can be improved through increased military spending is strong, but only if military spending is internal and not just pending on more imports. The US is an example of this theory working in practice because the US military imports minimal equipment and its military equipment producers are the single largest exporters of military equipment in the world.

Given that the EU has not achieved its own goal of having 35% of its own military procurement in European production, it is unlikely large European economies can militarize their way out of current economic difficulties. It’s all well and good wanting German automotive engineers and factories to switch to military production (DefenseNews.com) – and companies like Rheinmetall are making movements to make that happen – but if the increase in military spending ends up primarily going on further imports then it will simply not move the needle for the region. Instead, additional spending will simply benefit the suppliers, which for the overwhelming majority of military production are based in the US.

With so many comments from leading figures within the European Union stating that they can no longer rely on the US in terms of defense due to the current administration’s approach to the Ukraine-Russia war and perceived unpredictability in terms of foreign policy – especially the threat to pull the US out of NATO if Europe does not start increasing military spend – perhaps this will change. However, if the past 18 years are anything to go by, strong manufacturing growth through remilitarisation appears unlikely.

Interact Analysis’ Manufacturing Industry Output (MIO) Tracker forecasts out to 2028 and covers a total of 45 countries, across 72 manufacturing end user sectors, 30 machinery sectors and two points in the supply chain (machinery and manufacturing end-users).

Jack Loughney is a Senior Data Analyst at Interact Analysis. Jack works as the primary data analyst across multiple research activities. His expertise lies in data modelling, economic forecasting and streamlining processes to enhance product efficiency. Jack is responsible for the upkeep and enrichment of our MIO tracker.